Larissa Sansour 9.10.2024–2.3.2025

The past, the present and possible futures meet in Palestinian-Danish Larissa Sansour’s (b. 1973) darkly expressive exhibition, which opens up a space for new ways of thinking about Palestinian history, loss and trauma. Sansour’s carefully considered and aesthetically refined video works and installations weave historical and contemporary politics with imagined realities, using the narrative methods of sci-fi, documentary and opera. The exhibition at Amos Rex consists of seven of her works made between 2009 and 2022.

Sansour uses the speculative narrative and experimental visuals of sci-fi to probe the future and address the conflict in Palestine that has lasted for nearly a century, reframing the history of a people and a homeland on the brink of erasure. Sansour's own heritage and lived experience are the sources of her artistic practice. Her works evoke reflection and grow into universal studies of grief, memory, and inherited trauma.

At the heart of Sansour’s working process and oeuvre is art’s unique capacity to create new spaces for contemplation, to be a voice for silenced narratives. She is based in London and has a longstanding artistic partnership with the Danish visual artist and author Søren Lind. This exhibition is her first comprehensive solo show in Finland.

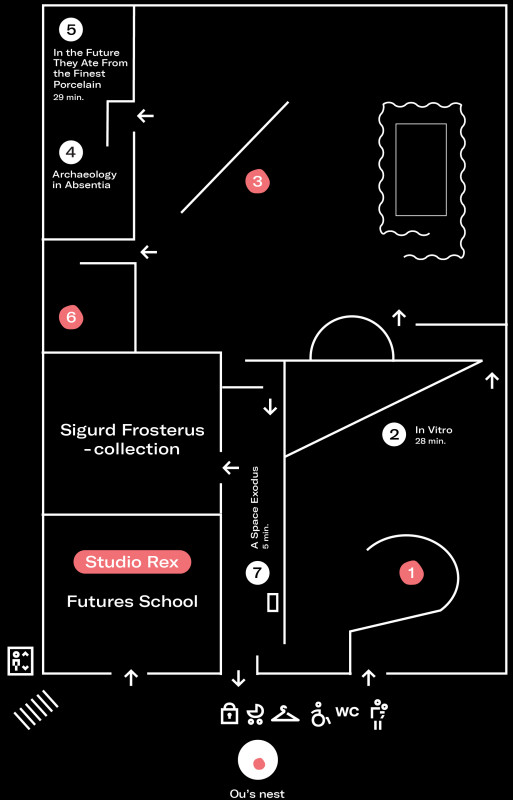

Kid's map

This map offers tips for those who are visiting the museum together with a child. We recommend teachers and pedagogues to navigate to our separate pages tailored to schools and preschools, which you’ll find here (the link opens in a new window).

Interview with Larissa Sansour

Larissa Sansour interviewed by curator Terhi Tuomi.

Terhi Tuomi: Your works deal with the power imbalances and voices of history, but also draw from your own personal history and lived experience. What is your background? What experiences have shaped your artistic practice?

Larissa Sansour: I was born in East Jerusalem and grew up in Bethlehem in Palestine, so I have experienced apartheid and the brutal Israeli occupation first hand. Throughout my practice I have been interested in the representation of marginalised voices and understanding how they fit in the Western canon. My own practice aims at subverting these structures and the violence of the image. Unfortunately, the misrepresentation of Palestine and Palestinian voices became painfully clear to me when I first moved to the UK in the late 80s. In the past decade, there was a general feeling of Palestine no longer being taboo, of a more reasonable and multi-faceted dialogue slowly emerging. But today, in the framework of the atrocities committed in Gaza and particularly the Western response, the very notion of civilisation as always moving forward and political dialogue constantly trying to ethically refine itself has suffered a major and very devastating blow. Rather than seeking to firmly and finally understand the situation and its history, the attempts at silencing the voices of not only Palestinians, but anyone advocating for justice and accountability, have never been more pronounced, and this fact only further encourages and inspires Palestinian artists like myself to keep working.

TT: Over the course of your 20 year-long artistic path, you have moved from a canvas to a lens-based practice from activist works to large-scaled film productions. What prompted these shifts?

LS: I was originally trained in painting, working both abstractly and figuratively, but with the widespread availability of video cameras, I became interested in the moving image, in large part also because of an increased focus on the political situation in Palestine. This shift came soon after I left university, and it coincided with the second Intifada in Palestine, which left me and other Palestinian artists with no other option than to try to make sense of what we were all witnessing. The camera became a tool for documenting the atrocities on the ground, driven by a sense of having to capture and archive what appeared at the brink of erasure. My initial filmic approach was documentary, chronicling people and places, conversations as well as the architecture of occupation. Soon, however, that approach seemed to leave a lot of central topics underexplored, so I turned to fiction in order to explore the concepts that were often left behind in favour of the brutality of the immediate present. I soon found that relocating to the future gave me a necessary distance to the present that allowed for further unpacking of the existential challenges of the Palestinian experience. Science fiction allows for a commentary on present day from a different angle, and since embracing that approach, my productions have escalated in both visual and conceptual scope.

TT: You have a collaborative practice, working with professionals from a variety of fields, and you also have a deep artistic dialogue with Danish artist and author Søren Lind, would you like to open the importance of collaboration?

LS: Working mainly with film, collaboration is essential to the development of new work. In early works, it was a very limited crew, friends and family as actors, a single camera, and I did the editing myself. But once the productions became more complicated, the core team organically expanded. My main collaborator is Soren Lind, who worked in the background as a producer and cameraperson on early works, but as soon as the projects required more extensive development, Soren started writing the scripts, while I did the visuals, and we began directing the films together. Today, our core team has expanded further to include a producer, a director of photography and a visual effects supervisor, and it’s within this group that most projects take shape, but the main conceptual and visual development are always done by Soren and me. Film is such a comprehensive undertaking that it requires collaborative efforts. It’s essential to the process. And that, of course, also means relinquishing that firm singular grip that many artists naturally prefer. While this leads to a certain loss of control, the work always benefits from being discussed and finessed in this larger forum, so this shared responsibility and commitment has long since become an integral part of how I work. With the work becoming more and more ambitious, the production teams have also increased – with In Vitro having a combined crew of more than 80 people across several international locations. That many people gathering forces to create a work together is really quite a rewarding experience.

TT: Your current exhibition at Amos Rex presents works from the last fifteen years. It is the first time your works are exhibited in a subterranean chamber - how does space and context affect your works?

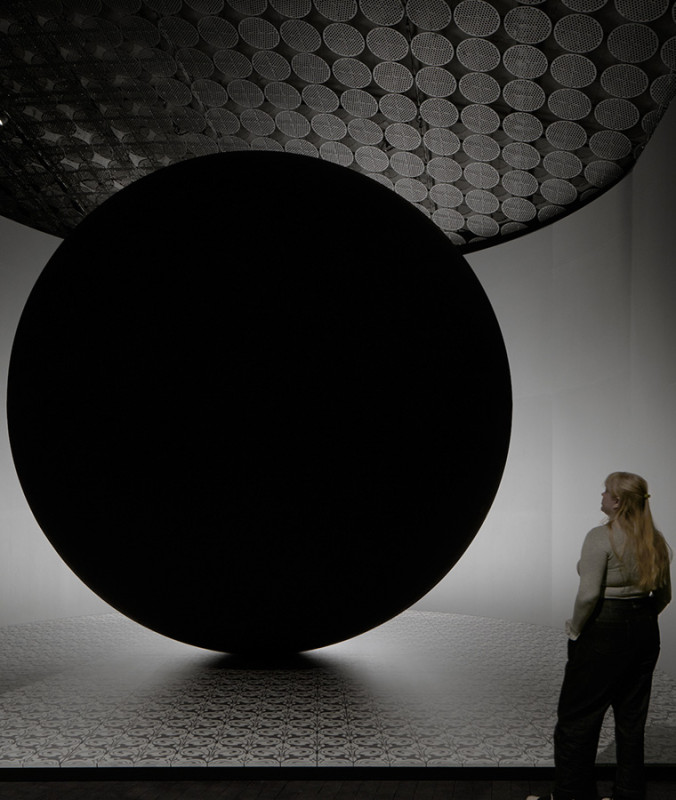

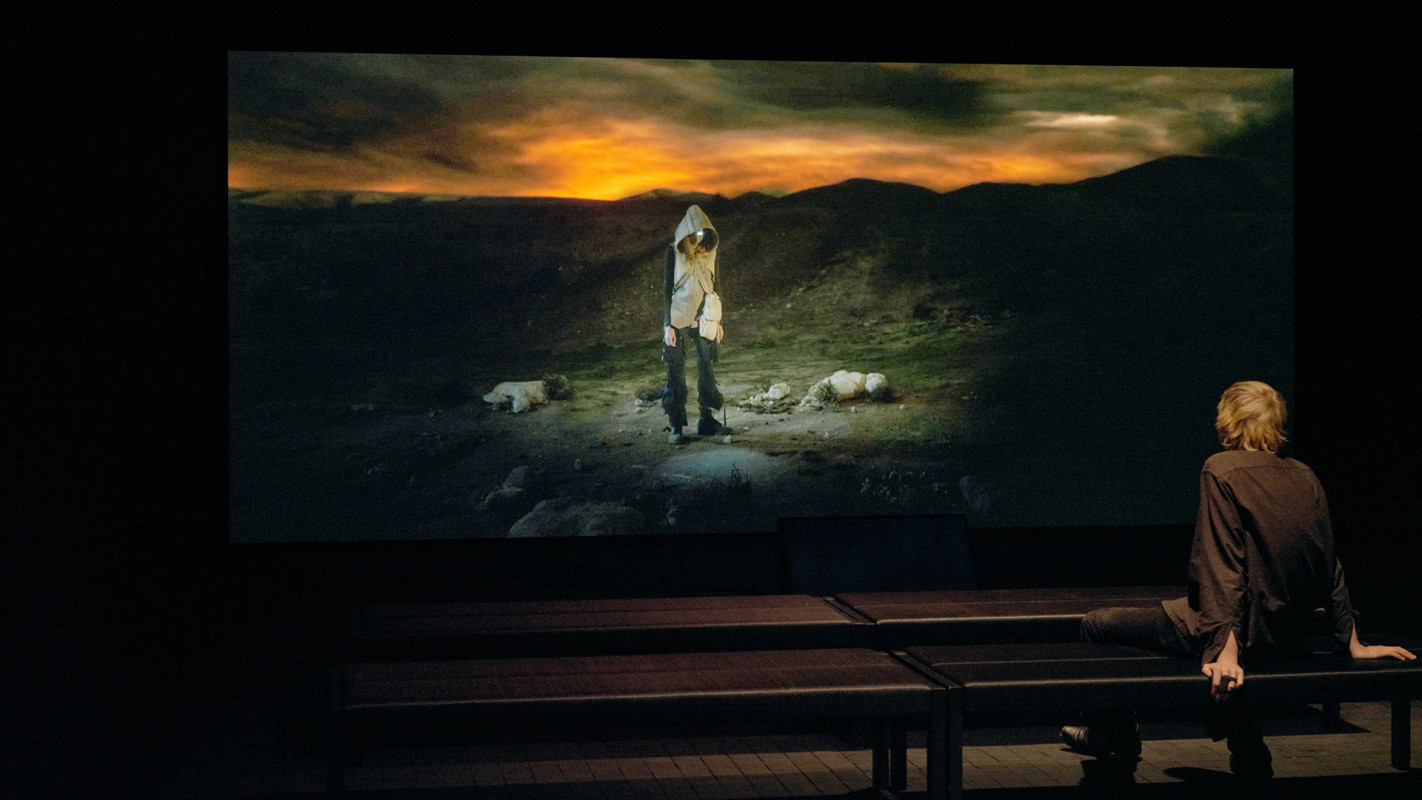

LS: As I’m sure other artists feel when they first visit Amos Rex, it’s an awe-inspiring space, and it seems perfectly tailored to the body of work that I will be showing. The size alone invites large-scale installations and film projections to come to their full potential. But more importantly, the architecture compliments defining details of the works presented. My film In Vitro is itself staged in an underground bunker, an unforgiving brutalist space with aspirations on the part of the protagonists to soon leave their subterranean hideout behind and move overground. The large spherical sculpture Monument for Lost Time fits comfortably with the curved ceiling, its dotted surface and round skylights. And the opera film As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night now plays out in its own underground concert hall, resonating in the vastness of the space, further accentuating its themes of loss, history and inherited trauma. The works themselves often convey a sense of claustrophobia and confinement, and this underground space both mirrors and negates those sentiments, reinforcing the sense of involuntary refuge while allowing the works to breathe.

TT: The political content in your works is evident, and in the exhibition, we encounter a big black sphere, the Monument for Lost Time, reminiscent of things that are left unsaid or unseen, from which we cannot escape and are forced to deal with. Has your relationship to your older works been affected by the tragic developments in Palestine?

LS: Yes, absolutely. In recent years, my work has focused on memory, loss and inherited trauma, all concepts summarising Palestinian history. I address the tragedies of the past, and the present being the past, there was always a degree of abstraction to that, augmenting a pattern of loss, rather than pointing to any singular event. But the ongoing tragedy only shows that the traumas of the Palestinian past are never further away than the immediate present. What we are witnessing now is unbearable, not only in terms of innocent lives lost, but also in terms of the ethical corruption of humanity. Looking at previous works now, I see them in a completely new light, with an added immediacy, certain dialogue fragments written in an equal air of mourning and premonition, which in itself only confirms the cyclicality of the atrocities and injustices committed in Palestine.

TT: What will be your next journey - what you are currently working on, and have the recent events influenced upcoming projects or plans?

LS: The ongoing tragedy in Palestine has influenced my practice in many ways, just as I imagine it to be the case for most other Palestinian artists. Shows have been cancelled, works have been censored, funding has become increasingly difficult. But at the same time, new opportunities to speak out and show the work have come about as well. My main focus these past couple of years has been the feature film that I am developing. It’s a sequel to In Vitro, and just like that film, it takes its point of departure in a major catastrophe and centres its narrative around the rebuilding efforts, a fundamental and very radical recreation of all things lost, land, cities, people, traditions and memories. In the light of the current tragedy, that setup takes on a whole new meaning, with the fictional disaster setting the stage for the film no longer seeming fictional at all. The urgency of this project has also increased, as the framework for the film, its focus on loss, memories and rebuilding, seems more acutely relevant than ever. Alongside the feature film project, I am also working on a large commission for the Wereldmuseum in Amsterdam, and this is also a project I am looking very much forward to, as it explores a relatively overlooked chapter of Palestinian history, namely the mercantile blossoming of particularly Bethlehem in late 19th century, an era of great promise and ambition. And again, historically remote as it may appear, this project has taken on an added degree of importance for me, as it narrates yet another omitted chapter of Palestinian history and creates a portrait of a people and a nation so rife with a potential eventually shattered by the British Mandate and the Israeli occupation that followed.

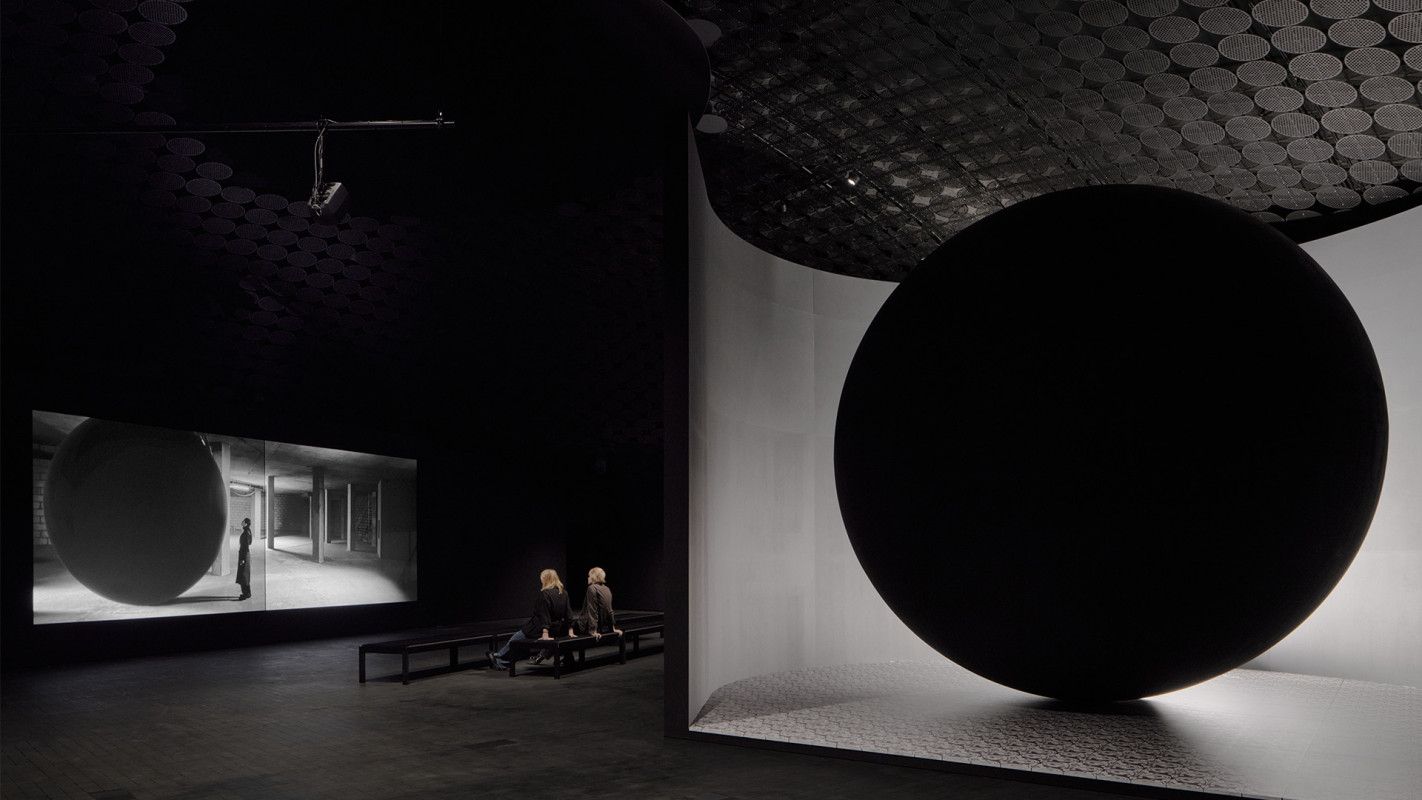

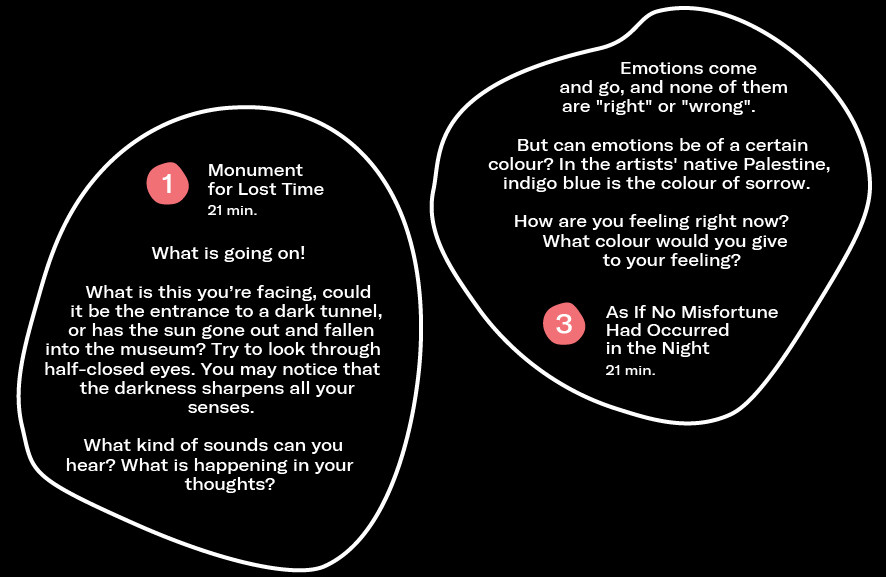

1. Monument for Lost Time

![]()

Larissa Sansour, Monument for Lost Time, 2019. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

1. Monument for Lost Time

2019

sculpture

diameter 4.8 m

materials: concrete, metal, paint

audio 4.1.

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind

A large, black spherical object, hidden from direct sight, waits for the viewer in the exhibition space. A sound originating in low-frequency vibrations resonates around the motionless monument and settles deep inside the viewer’s body like a trauma. The sculpture is so impenetrably black that it reflects no light at all, creating an optical illusion. With our sense of sight alone, it is virtually impossible to envisage the three-dimensional nature of this profound blackness, accentuating its pervasive, menacing quality that is as hard to grasp as a complex emotion.

Monument for Lost Time was first shown together with the film In Vitro at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019. The works were commissioned from Sansour and the Danish visual artist and author Søren Lind by the Danish Arts Foundation. The mysterious sphere appears in the film as a fictitious, psychologically charged entity, while in the exhibition space the cinematic object is turned into a physical fact, like the embodiment of an inherited trauma. The monument stands on a plinth covered in patterned tiles like those seen in a scene from In Vitro where a girl sits on the floor of her home, which she and her mother are forced to leave when a disaster destroys their entire city.

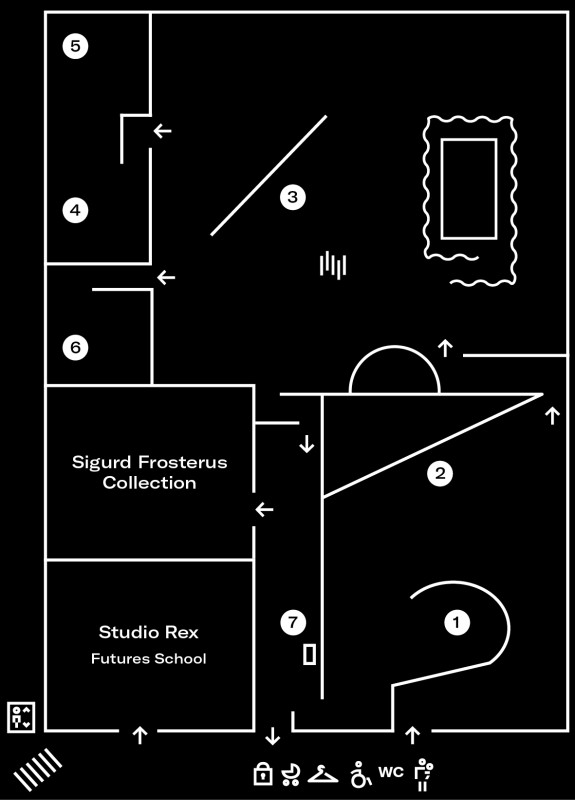

2. In Vitro

![]()

Larissa Sansour, In Vitro, 2019. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

2. In Vitro

2019

2-channel film, 28 min.

audio 7.1

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind

In Vitro is an Arabic-language, black-and-white sci-fi film set in the biblical city of Bethlehem, decades after an environmental disaster. Beneath the city is an abandoned nuclear reactor, which has been converted into an enormous refuge and orchard. There, a group of scientists are preparing to restore life on Earth with the aid of heirloom seeds collected before the apocalypse. The Latin title, In Vitro, literally means “in glass”. It refers to scientific procedures that take place outside a living body, in an artificial space. By setting the events in the aftermath of an eco-catastrophe, Sansour places her work in a context that resonates widely in our time.

The two-channel video features an intense dialogue between Dunia, who founded the orchard and who represents an old, bygone age, and her young successor, Alia. Emblematic of a new era and new opportunities, Alia is a clone of Dunia’s deceased daughter. She was born and raised in laboratory-like conditions underground and has never seen the city she is about to replant and repopulate.

In In Vitro, time does not seem to be linear, rather, all the different layers of time are present simultaneously. The film continues Sansour’s exploration of loss, heritage and inherited trauma as well as her research into epigenetics, a discipline that studies the transmission of trauma between generations at the genetic level. Alia’s memories of the distant past are not her own, but rather implants from the person she replaced. The dialogue loops back and forth between past and future: how much of the past and of memory is worth carrying forwards, and who decides?

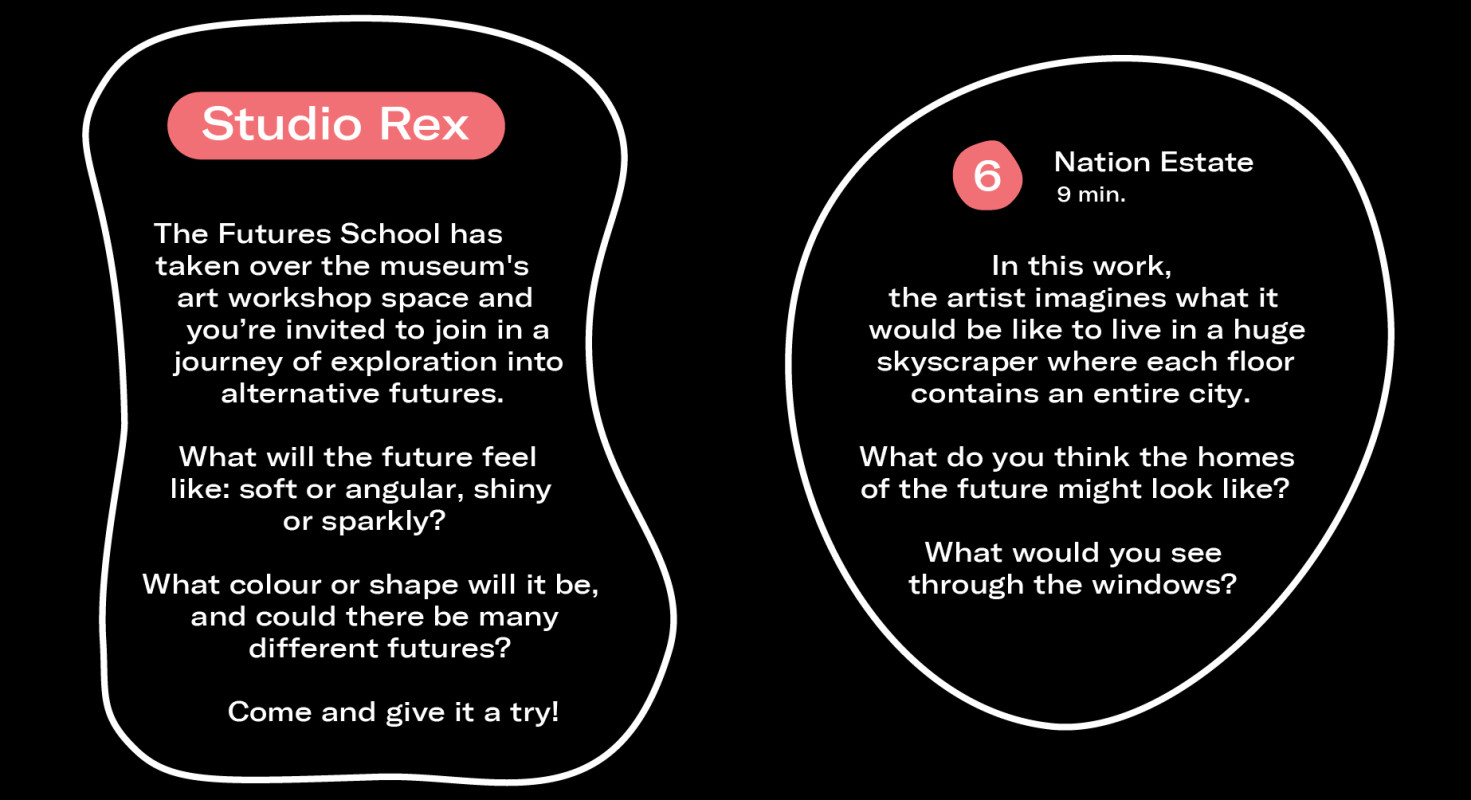

3. As if No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night

![]()

Larissa Sansour, As If No Misfortune Had Occured in The Night, 2019. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

3. As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night

2022

3-channel film, 21 min.

audio 7.1

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind

As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night lends an untraditional form to Sansour’s exploration of inherited trauma and epigenetics. At its centre is an Arabic-language opera about trauma, loss, and mourning, seen in a black-and-white three-screen projection, arranged like an altar triptych.

The aria is performed by Palestinian soprano Nour Darwish and composed by the Lebanese composer Antony Sahyoun. It is based on the Austrian Gustav Mahler’s composition Kindertotenlieder and the traditional Palestinian song Al Ouf Mash’al. Kindertotenlieder, which premiered in 1905, set to music a group of poems written by the poet Friedrich Rückert after the death of his two children. In Al Ouf Mash’al, a Palestinian woman mourns the loss of her lover, who was recruited into the Ottoman army in World War I. The aria blends together two different musical traditions, weaving a beautiful lament for more than a hundred years of grief.

Filmed in a derelict chapel, the opera juxtaposes computer generated imagery and archival footage of the First World War. As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night uses documentary material from the Imperial War Museum in London, including scenes from Palestine at the start of the British Mandate and from the struggles against the Ottoman Empire.

In the opera’s final scene, the singer immerses herself in an indigo pool, changing the colour of her white dress into the shade of blue historically associated with mourning in Palestine. Indigo is physically longer lasting than other pigments and like grief, it stands the test of time. The world of the opera flows from the chapel into the exhibition room in the form of an installation surrounded by indigo curtains, with silent tree trunks resembling dismembered bodies hanging over the pool on chains from the ceiling.

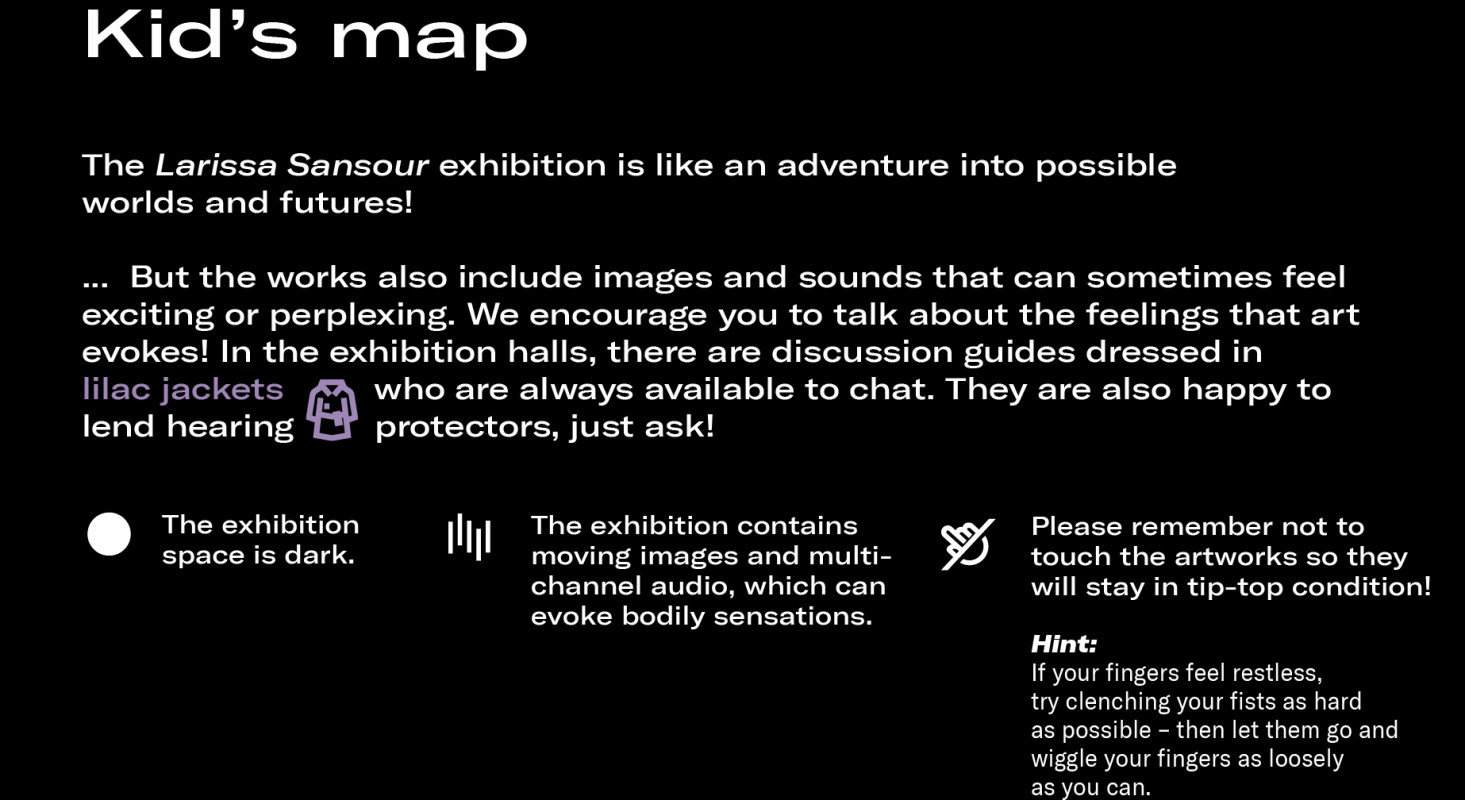

4. Archaeology in Absentia

3. Archaeology in Absentia

2016

10 sculptures,20 cm x 10 cm

material: bronze

4 Photographs, 30cm x 40 cm

1 Photograph 60cm x 80cm

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind

Archaeology in Absentia is a sculptural installation consisting of ten bronze munitions. Inside each of them is a disc engraved with the coordinates – longitude and latitude – of locations on Palestinian and Israeli soil where the artist has buried porcelain plates hand-painted with the traditional Palestinian resistance pattern. Accompanying the sculptures is a series of photographs taken at these locations.

With the help of local art institutions, Sansour originally buried 15 physical plates in the places indicated by these coordinates, including in the cities of Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Acre, Haifa, Jericho, Jaffa, Nazareth, and the Dead Sea. The bronze munitions are modelled on a Cold War-era Russian nuclear bomb. Opening up like Fabergé eggs, they and the coordinates represent archaeological artefacts in absentia (not present).

The Archaeology in Absentia sculptures embody the idea of weaponised archaeology used to settle territorial disputes and support historical entitlement to the land. Throughout history, archaeological finds have been co-opted to reinforce prevailing narratives. These sculptures are displayed in a way that recalls the traditional museum practice of keeping valuable artefacts in display cases as historical evidence of the past. Here, however, the display case contains location codes for artefacts that have yet to be excavated – eventually causing a historical intervention.

Archaeology in Absentia is conceived as a performance inspired by the film In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain.

![]()

Larissa Sansour, Archaeology in Absentia, 2016. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

5. In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain

![]()

Larissa Sansour, In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain, 2009. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

4. In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain

2016

1-channel film, 29 min.

Audio stereo

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind

In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain is a film that occupies the point of intersection between science fiction, archaeology and politics. It explores the influence of myths and narratives on the formation of history, facts, and national identity, combining cinematic narrative with computer animation.

The story follows a resistance group that buries fragments of porcelain tableware with the aim of creating a new, fictional civilisation for future archaeologists to discover. The group seeks to influence the prevailing narrative of historical events and to enable future generations to reclaim their own land: when the buried porcelain is excavated, it will serve as evidence of the existence of an imaginary people. The film interrogates issues of history and power: who gets to write history, whose voices get to be heard?

The dialogue here is between a psychiatrist and the female leader of the resistance group. The hypnotic landscapes and highly charged portraits contain diverse references to images from Palestinian cultural history. Some of them, such as the Keffiyeh pattern painted on the porcelain plates, are also repeated in Archaeology in Absentia. But, unlike the absent porcelain in the sculptural work, the painted plates visually appear in the film. The large bombs falling from the sky resemble the bronze sculptures in the museum display case, but instead of coordinates, hidden inside them is evidence for the future, the finest porcelain, raining down and covering the ground of the shimmering landscape. Together, these two works take our thoughts to the power of storytelling: how long does it take before fiction turns into historical fact?

6. Nation Estate

![]()

Larissa Sansour, Nation Estate, 2012. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

6. Nation Estate

2012

1-channel video, 9 min.

audio stereo

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour

Nation Estate is a film set amid sci-fi imagery that takes a dark-humour-tinged, but utterly dystopian approach to the political deadlock in the Middle East. It combines a computer-generated world with live actors and an electronic, Arabic-language soundtrack. The story suggests a vertical solution to the creation of an independent Palestine: Palestinians have their own state – a giant skyscraper called the Nation Estate.

The viewer follows the main character, acted by Sansour herself, from a railway station to the 21st floor of a block of flats, the Bethlehem floor. The adverts in the skyscraper’s lift range across various social and political issues affecting Palestinians, including access to water and travel restrictions. The rooms here are inspired by sci-fi imagery and refer to important landmarks, such as the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The story takes viewers into the main character’s home, which is teeming with cultural references, for instance, to embroidery, food, and national symbols. The apartment’s glass wall opens onto a panoramic landscape, which, at the press of a button, can be transformed into a view of Jerusalem.

All the Palestinian cities and the different sectors of society are on different floors of this massive building. At last, the entire Palestinian people can live a peaceful life together – but still within walls.

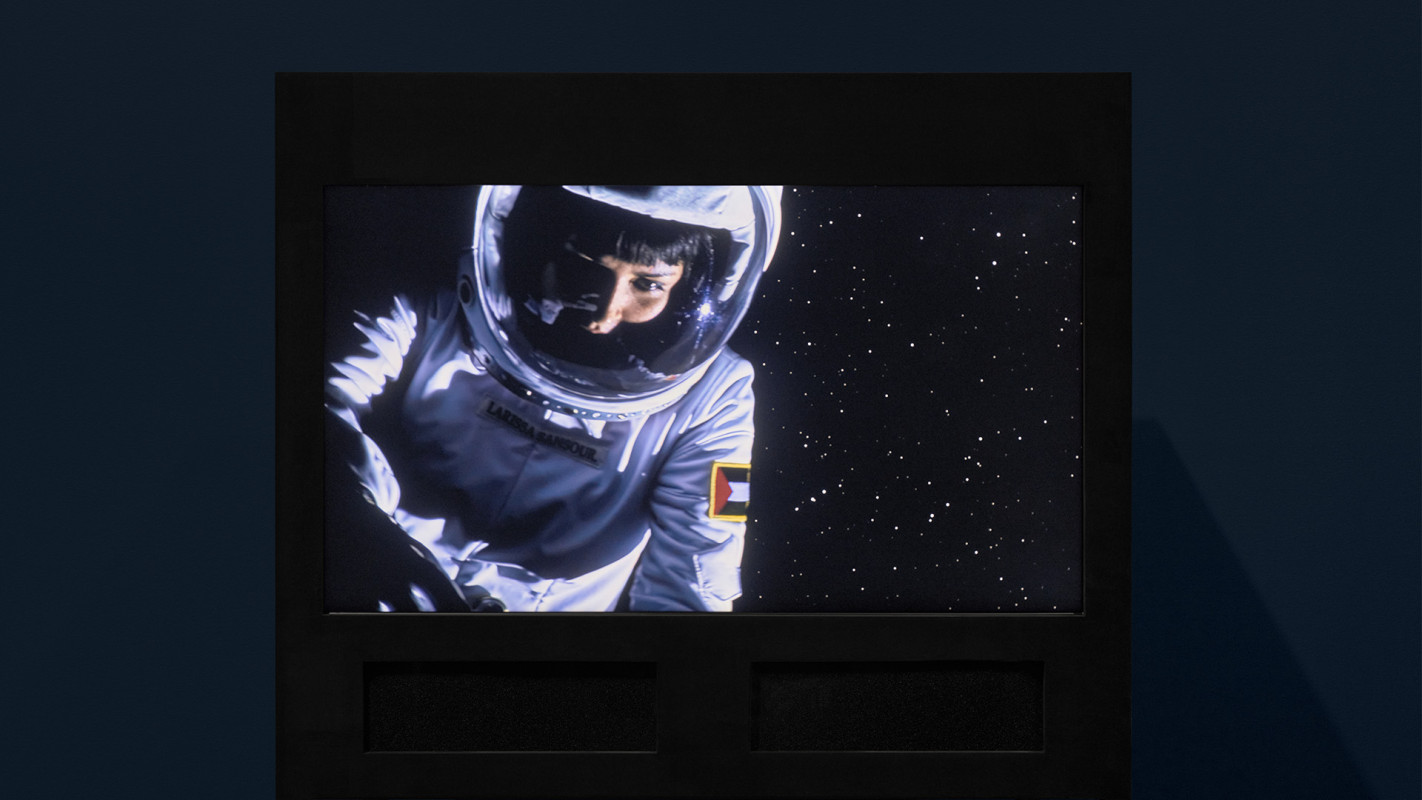

7. A Space Exodus

![]()

Larissa Sansour, A Space Exodus, 2009. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

7. A Space Exodus

2009

film, 5 min.

audio stereo

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour

A Space Exodus quirkily transposes the imagery of Stanley Kubrick’s iconic 2001: Space Odyssey to the context of the Middle East. The familiar music of Kubrick’s 1968 sci-fi film is transformed into an Arabic-style soundtrack to match Sansour’s outer-space visual world.

The story follows Sansour herself on an imaginary journey through the universe, accompanied by Kubrick’s themes of human evolution and technological development. Here, however, Sansour raises the novel idea of the first Palestinian in space, in a reference to Neil Armstrong’s 1969 moon landing. She rewords the historic event: “A small step for a Palestinian, a giant leap for mankind.”

A Space Exodus offers a speculative alternative way for Palestinians to have their own territory. Perhaps there could finally be a place in outer space belonging to Palestinians, and under just one flag.

Familiar Phantoms screening on 26 February

8. Familiar Phantoms

2023

film, 42’

Courtesy of Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind

Familiar Phantoms is an experimental documentary short film about memory, history and trauma. It explores the impact of fiction and stories on the creation and reinterpretation of memory. It seamlessly combines film, narrative, special effects, family photos, and archival footage. These fragments and gaps form a narrative interweaving illusion and fact.

The film is Sansour’s most personal to date and has been inspired by her own family history and her childhood in Bethlehem. Slow, fluid scenes and tightly edited collages of objects, mementos, family photos and Super-8 footage alternate, shot both in the studio and in a derelict mansion. The editing and visuals mimic the actual workings of memory; revisiting the same imagery, objects and spaces, seeking out their meaning and place in a fragmentary collage, like as yet unnamed phantoms.

Familiar Phantoms will be screened at Bio Rex on 26 February. Details are on Amos Rex’s website.

Glossary

The glossary provides a larger context for seven selected concepts featured in the exhibition texts. Parts 1-4 concern key moments and expressions pertaining to the political history of Palestine and has been compiled in collaboration with Timo R. Stewart, Senior Research Fellow at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs. All sources are listed at the end of the glossary.

1. British mandate

Britain conquered much of the Middle East during the First World War from the Ottoman Empire, which had ruled it for centuries. After the war ended in 1918, the League of Nations granted mandates to Britain and France to divide the conquered territories between themselves and guide them towards independence. Palestine fell under British mandate. As part of its mandate in Palestine, the British government made a promise to the Zionist movement to support the establishment of a 'national home' for the Jewish people. This was the aim of the Zionist movement, but the Arab majority of the Palestinian population wanted independence for the entire Mandate area. These opposing aspirations created constant conflict, which Britain was unable to resolve. The British Mandate in Palestine was formally announced in 1923. It ended with Britain's withdrawal in May 1948, in the middle of the civil war that broke out after the Partition Plan for Palestine was adopted by United Nations (former League of Nations), planning to divide the territory into Jewish and Arab sovereign states.

2. East Jerusalem

Jerusalem became a divided city in the 1948 war. The newly established Israeli army occupied its western neighbourhoods, while Jordan took the old city and the neighbourhoods to the north and east. The period of city division lasted until June 1967, when Israel occupied the entire Jerusalem area and the surrounding West Bank. These parts of Jerusalem occupied by Israel since 1967 are known as East Jerusalem. East Jerusalem has a majority Palestinian population, but Israel has been establishing settlements there since 1967. A large number of Israeli Jews have moved to these settlements in the occupied territory, which are deemed illegal under international law.

3. Nakba

Palestinians call the events surrounding 1948 al-nakba, Arabic for "catastrophe". For them, the nakba refers both to the establishment of the state of Israel itself, as well as the widespread exile and destruction of the Palestinian community that began during the war preceding and following the establishment of the Israeli state. During the 1947–1949 war, more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs, almost two-thirds of the population, fled or were driven from their homes. During the war, Israel occupied 78 percent of the former British Mandate in Palestine, while Jordan and Egypt occupied the rest. Israel did not allow the Palestinian refugees to return, and destroyed hundreds of deserted villages and repopulated empty neighbourhoods in towns and cities. A Palestinian state was never created.

4. Israeli occupation

In June 1967, Israel seized East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights from Jordan, Egypt and Syria during the so-called Six Day War. Sinai was returned to Egypt following a peace agreement signed in 1979. In contrast, Israel continues to occupy the rest of the territories that it seized in 1967. East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are referred to as the collectively occupied Palestinian territory because they were once part of the British Mandate in Palestine. In July 2024, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion stating that Israel's occupation of this territory is illegal in its entirety.

5. Epigenetics

Epigenetics is a branch of genetics that studies different mechanisms that influence gene expression without changes in the DNA sequence. Epigenetic inheritance occurs through so called epigenetic “tags”. An epigenetic tag can be formed in a particular gene as a result of both intrinsic and external factors such as psychological stress, exposure to toxins or nutritional deficiency. The epigenetic tag encodes the pattern of how the gene responds to its environment – whether the gene’s activity is “amplified” or “silenced” - which in turn influences how the individual reacts to their environment. The information of the epigenetic tag can pass from parent to offspring across several generations, shaping certain physical or behavioural characteristics, as well as susceptibility to certain diseases. In other words, epigenetics describes the mechanisms whereby a child is prepared to navigate the same living environments that shaped the parents, or even grandparents. Experimental studies have demonstrated the phenomenon of epigenetic inheritance in animals. Cross-generational population studies have also shown strong evidence of epigenetic inheritance in humans.

6. Keffiyeh

The Palestinian kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة), keffiyeh, is a square embroidered head scarf typically made of white cotton fabric. The embroidery is usually black or red. The keffiyeh and its patterns can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia (c. 3100 BCE). According to legend, Sumerian fishermen placed a fishing net on their heads to seek protection from the summer sun. Over time, this practice evolved into the distinctive headgear that we now know as Keffiyeh with its distinct fishnet-pattern. Worn primarily by bedouin men in several regions across the Middle East for centuries, the keffiyeh only emerged as a unified symbol for Palestinian liberation in the early 1900s. As the First World War ended in 1918, Palestine fell under British rule, which was met with popular resistance. Anti-British activities were led by Palestinians predominantly from rural areas, whose dress of choice was the black-and-white keffiyeh. While the keffiyeh had not figured in the dress-codes of middle- and higher classes, as desire for liberation spread, Palestinians of all social standing soon adopted it as a symbol of unity. The symbolism of the keffiyeh and its patterns have continued to develop ever since, encompassing the Palestinian struggle for independence and resistance against ongoing Israeli occupation.

7. Sci-fi

Science-fiction, or sci-fi, is a form of fiction dealing with the impact of actual or imagined science upon society or individuals. While expansive and fluctuating in nature, science fiction often considers themes of space- and time travel, utopias and dystopias, sex and gender, alien encounters, alternate histories and parallel universes. The historical roots of the genre are contested but have commonly been traced back to the Western Renaissance of the 16th century, when the social ramifications of European colonialist projects and scientific advancements such as the Copernican revolution began to bleed into the fiction of the time. The industrial revolution, emerging in the late 1700s and unfolding over the next few centuries, would manifest the genre as we know it today. Recently, scholars have challenged this western-centric narrative, pointing to historically parallel literature of the global East and South invested in narrating alternative realities and futures. As a speculative genre, sci-fi changes the laws of what is currently considered real or possible, and then speculates on the possible outcome - what if? Science fiction is thus experimental, allowing thought and imagination to move freely as present beliefs and commonsense are momentarily set aside. The artist Larissa Sansour has said that sci-fi allows her to single out details of the present and address them anew, free from their current meanings; to “talk about the present without being dictated by the current political jargon”.

Printed sources

Banerjee, A. & Fritzsche, S. (2018). Science Fiction Circuits of the South and East. New York: Peter Lang.

Juusola, H. (2004). Israelin historia – 2nd edition. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Kincaid, P. (2011). "Through Time and Space: A Brief History of Science Fiction". In: Sawyer, A., Wright, P. (eds) Teaching Science Fiction. Teaching the New English. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Khalidi, R. (2024). Palestiina — Sata vuotta asutuskolonialismia ja vastarintaa 1917-2017. Helsinki: Teos. Pappe, I. (2006): The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London: Oneworld Publications.

Morris, B. (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pappe, I. (2006): The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London: Oneworld Publications.

Online sources

Chang, A.; Dorning, C.; Mohammad, L. (4.12.203). How the keffiyeh became a symbol for Palestinian liberation. National Public Radio. Retrieved 7.10.2024, npr.org/2023/12/04/1217090817/how-the-keffiyeh-became-a-symbol-for-palestinian-liberation

Encylopaedia Britannica. Entry: science fiction. Online publication. Updated 21.9.2024. Retrieved 10.10.2024, britannica.com/art/science-fiction.

Das, R. (3.3.2024). The Story of the Keffiyeh. The Markaz Review. Retrieved 2.10.2024, themarkaz.org/the-story-of-the-keffiyeh/

Downey, A. (6.4.2020). Epigenetics and Speculative Research: In Conversation With Larissa Sansour. The MIT Press Reader. Retrieved 9.10.2024, thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/epigenetics-and-speculative-research-larissa-sansour/

Infante, D. (24.9.2024). The Role of Epigenetics in Human Disease. News Medical. Haettu 10.10.2024, news-medical.net/health/Understanding-The-Role-of-Epigenetics-in-Human-Disease.aspx

Peltoniemi, T. (4.12.2019). Isovanhempiemme huonot kokemukset voivat näkyä geenitasolla epigeneettisinä vaikutuksina jopa kolmanteen sukupolveen saakka. Yle.fi. Retrieved 9.10.2024, yle.fi/aihe/artikkeli/2019/12/04/isovanhempiemme-huonot-kokemukset-voivat-nakya-geenitasolla-epigeneettisina

Raitakari, O.; Kotaja, N.; Karlsson, H. (2021). Epigeneettinen periytyminen sukusolulinjassa. Lääketieteellinen Aikakauskirja Duodecim 137(8). Retrieved 9.10.2024, duodecimlehti.fi/duo16177