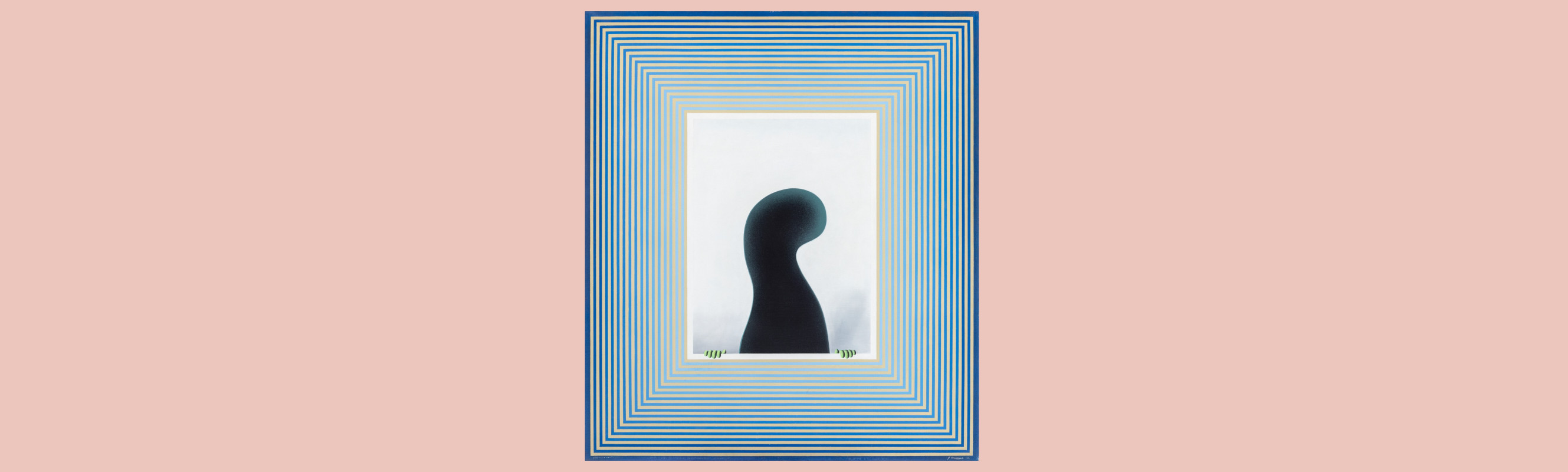

I Feel, for Now 27.3.–8.9.2024

The first major exhibition showcasing works from Amos Rex’s own collections takes us directly into our emotions. One artwork can provoke a surprising, instantaneous emotional response, while another can induce a feeling that creeps up on us more gradually. Art moves us, or not, in ways that we ourselves do not always quite understand, let alone know how to put them into words. Whatever we feel when faced with works of art, perhaps we could approach them with the same attitude as the intriguingly indefinable creature in Juhani Linnovaara’s Curious: leaning forwards, senses open.

The title of the exhibition refers not only to Kari Cavén’s ambiguous artwork, but also to the fluidity and ephemerality of emotions. The themes of the exhibition also converge, forming criss-crossing paths that any of us can walk along, while remaining alert to our own experience. Accumulating and displaying the works in a collection always involves an exercise of power; the choices made inform later art history, and hence our understanding of the world around us. These power constellations are interwoven into the numerous interpretations that different people make when they encounter the works chosen for an exhibition. In the midst of art, the feelings of museum workers and visitors are intertwined.

Föreningen Konstsamfundet’s art collection is managed by Amos Rex and comprises more than 6 000 works. It is based on the body of some 400 artworks built up by the businessman, newspaper publisher and patron of the arts Amos Anderson (1878–1961). His home museum, Amos Andersons Hem, which opened on Yrjönkatu Street in spring 2023, shows mostly older works from the collection. The period spanned by the more than a hundred works now on display at Amos Rex extends from the 1960s to the present. Also radiating its own light underneath the second dome is the newly commissioned, participatory artwork Spirit Systems of Soft Knowing by the artist collective Keiken.

Exhibition Map

Beneath the Surface

![]()

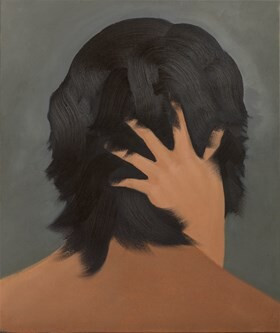

Henni Alftan: Darling, 2014

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex

In Henni Alftan’s Darling, the fingers running through the black hair of the figure with its back to us raise a question. This enigmatic hint of another person’s presence or absence gives the painting a powerful emotional charge. The essential element of an artwork – the mood, the state of mind or the memory that it communicates to us – is often the very aspect that is not visible.

The mind, too, has its own deeper, subterranean landscape that we do not necessarily reveal to others straight away. It is on this level that we may, for instance, experience restlessness, loneliness, or fear of abandonment. In the middle of the climate crisis, many of us are also feeling a profound sense of hopelessness that will not give us a moment’s peace of mind. Roland Persson’s The Last Horse on Earth seems to be a dystopian image of a world that has undergone an ecological catastrophe, but this horrifying, silicone-coated image of the future may be more topical than we dare to admit.

Emotions influence everything we do and, if they last, merge into moods. But individual emotional states are transient – they do not permanently define our existence. There is no right or wrong way to experience feelings, but when suppressed and ignored, they eat away at both body and mind. Making and experiencing art can help us identify, regulate, and understand emotions that can be quite abstract and complex.

A Moment of Ecstasy

![]()

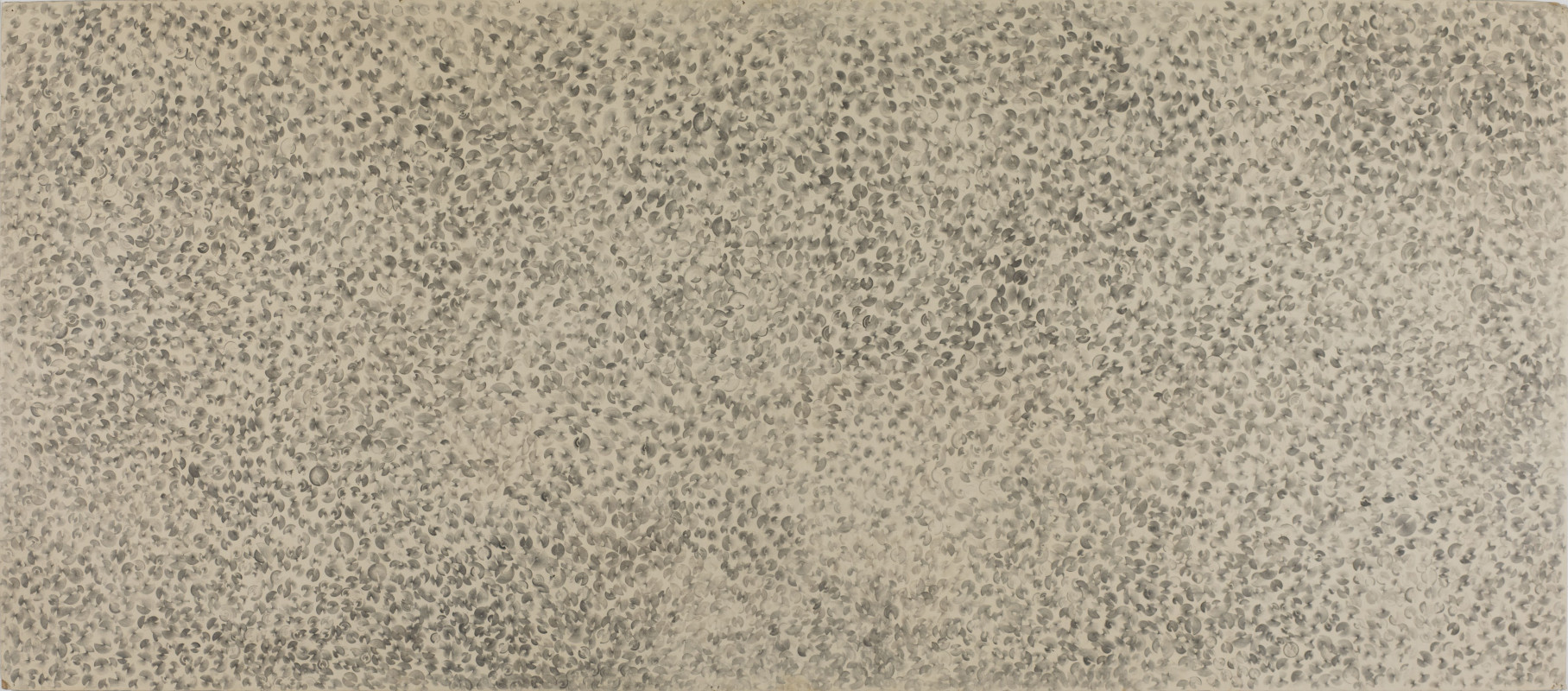

Jan Olof Mallander: Wang, 1981

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex

Amos Anderson, who was brought up in a religious family, was interested in Catholicism and Church history, and in 1926 even had an entire chapel, with artworks and an organ, built inside his home. In its own way, Jan Olof Mallander’s charcoal Wang carries on this spirituality-driven thinking. When viewing it, our gaze, as if, turns inwards, as it traces the recurring shapes on paper. The museum’s background noise fades and our minds become calm. In Tibetan Buddhism, a wang is a ritual and a transmission of energy.

Art can even evoke uncontrollable feelings and deeply move those who experience it. In the famed Stendhal Syndrome, an encounter with art can be so ecstatically intense that it induces physical symptoms, such as nausea, fits of weeping, or palpitations of the heart. This experience that transcends the individual’s understanding has been compared both to being touched by God and to a migraine, but its origins lie in the emotion triggered by a work of art.

Emotions are again difficult to describe in the biblical scene in Kari Vehosalo’s painting The Corruption of the Working Class (greatest is love), which has something indefinably unsettling, at once familiar and strange, about it. In this moment frozen with photographic precision, we can get a glimpse of a web of meanings rooted in art history and religious culture, a web that creates strange, suggestive nuances, as if by stealth.

Memory Games

![]()

Stiina Saaristo: Last Man Standing, 2007-2008

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex

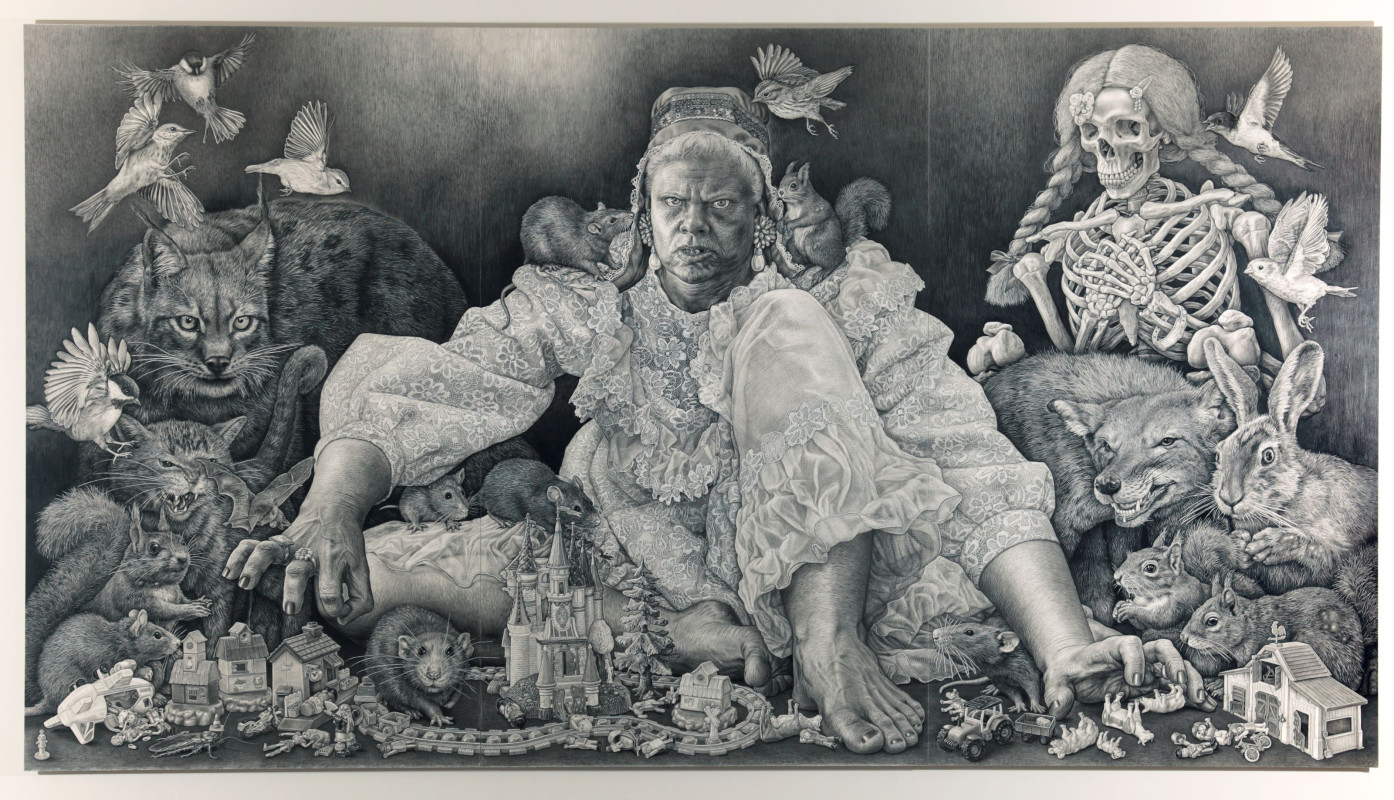

In Last Man Standing, a large pencil drawing by Stiina Saaristo, the protagonist of the story sits in the middle of a rickety toy town surrounded by forest animals. This human figure is a mixture of an adult who has seen a lot of life and a child who still plays with toys. The scenario and the figure’s piercing gaze contain elements of menace, while the work simultaneously exudes an atmosphere familiar from childhood and its fairytale worlds.

The word nostalgia originally meant homesickness. Nowadays, it is used more broadly to refer to any sort of longing for the past. The experience of nostalgia is often associated with wistfulness or melancholy, and sometimes even dejection, but positive emotions, such as joy, warmth and a feeling of being loved, are also frequently present. Sometimes, nostalgia is used as a tool for influence that harks back to the good old days in populist discourse or rhetoric aimed at consumers.

Identical issues and situations that we face time and time again can feel dull or stupefying. Life is, in fact, full of repetition: summer holidays, hobbies, morning meetings, carrot purée, and bedtime stories that we know by heart. As a contrast to routines, everyday life is also made up of disorder, surprises and unpredictability. In Perttu Näsänen’s painting Zigzag 14, blue elements fall at various angles inside a grid of squares. Amid this geometric play, even chaos is ultimately controlled, occurring within the limits of the gaze.

Emotional Language

-

![]()

Tommi Toija: Strangers, 2011

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex -

![]()

Tommi Toija: Strangers, 2011

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex -

![]()

Tommi Toija: Strangers, 2011

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex -

![]()

Tommi Toija: Strangers, 2011

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex -

![]()

Tommi Toija: Strangers, 2011

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex -

![]()

Tommi Toija: Strangers, 2011

Photo: Stella Ojala / Amos Rex

Expressing thoughts and feelings through language can involve writing a diary, swearing when you hit your thumb with a hammer, inventing pet names for your children, or even giving your true opinion in a work meeting. Language, and especially our native tongue, is often a strong thread woven into our feelings, but non-verbal forms of communication, such as gestures and facial expressions, also signal emotions.

In the multidisciplinary installation Spirit Systems of Soft Knowing by the artist collective Keiken communication between humans and other species is made a reality using the sense of touch and non-verbal sounds. The awareness of all the ways in which we cannot directly communicate to other creatures gives way to a momentary harmonious coexistence or even co-cocooning with other living things. Empathic connection can suddenly seem even more important than intellectual understanding and verbalization.

The lost-looking figures in Tommi Toija’s Strangers series, with which we instinctively identify on some level, also communicate without words. The emotions on the faces of these sculptures that view the world with various shades of wonder offer us a kind of tragicomic surface in which to mirror ourselves. Toija’s little creatures allow us to sympathize and to process painful issues – alone, and yet together.

Carried Away by the Senses

Our visual sense is often primary when experiencing art – partly because we are rarely permitted to touch the works in an exhibition. But we still form interpretations and meanings with all of the senses at our disposal. The haptic, i.e. tactile, remembered impressions left by the materials are intense and also steer our expectations when we are viewing art. An unexpected material switch can be confusing, when something soft turns out to be hard or sharp, or when a familiar shape does not suit its usual purpose.

Many artists have been inspired by material experiments and the use of readymade objects and materials, including Kari Cavén. In Cavén´s work I Feel, for Now, our attention is initially drawn specifically to the differences between the materials in the distinct parts of the work. Nevertheless, its title, which revels in the ambiguity of language, opens up an endless series of interpretations. In the Finnish title, musta can refer both to the experiencer, the self, and to the colour black. The work and its title invite us to listen not only to how we feel at this moment, but also to the emotions evoked by the colours and materials.

Black also dominates in Oona Tikkaoja’s Fungus, a sculpture which looks as though it had fallen from outer space. The rubber surface dotted with screws and nuts, and especially its distinctive smell, may even be repellent to some people, or make them uncomfortable, while for others it may make them feel good in a tantalizing way – or all of these sensations at once. Physically felt emotional and sensory reactions are quite primitive or uncontrollable, and emotions seen as being opposites can also coexist.

![]()

Oona Tikkaoja: Fungus, from the series Yuggoth, 2006

Photo: Stella Ojala

Spirit Systems of Soft Knowing ༊*·˚

Keiken

founded 2015

Spirit Systems of Soft Knowing ༊*·˚

2023–2024

silicone, haptic technology, LED lights, soundscape, fabric, wood, cushions, video mapping

Photo: Niclas Warius / Amos Rex

________________________________________________________________

Spirit Systems of Soft Knowing ༊*·˚ by the artist collective Keiken, explores the idea of extending empathetic connection and communication towards other species and other forms of existence. This tactile, spatial installation draws on the body’s energy currents and on material animism, a philosophy rooted in the idea that all creatures and things possess a soul. The experiences and bodily sensations of museum visitors become a continuation of and complement to this immersive work.

Visitors are invited to step into the glowing, curtained-off installation. Once inside the shell-like spiral space, visitors can lie down on one of the four beds, which together form a meditative reef. The organic shapes are mirrored in the cluster of cushions on the beds, inspired by naturally occurring seed pods. Gazing upwards into the cavernous ceiling, visitors encounter a vibrating, star-like energy source that casts its radiance onto the space.

Museum guides accompany visitors into the installation and assist throughout the experience. The wearable artwork – a silicone womb – is placed on each visitor and becomes an artificial extension of their physical body. The delicate vibration of the glowing blue womb against their abdomen, together with the sounds of life channelled into their ears through the headphones, open up a multitude of possible portals for the imagination.

Shimmering in the airflow, an umbilical cord-like link connects the space to the pulsating nebula above. The different elements of the work are tied together by a spatial underwater soundscape. The installation seeks to tune in to a non-verbal connection with different forms of existence, forms that may not even be attainable on a verbal or intellectual level.

Expanding the Senses

The collective sees the wombs as “tools of consciousness” that can be used to create an empathetic connection with the unknown. The background research for the piece is based on neuroscientist Paul

Bach-y-Rita’s studies, which focuses on expanding the senses. Bach-y-Rita discovered that the neuroplasticity of our brain allows it to be rewired. Keiken investigate ways of using technology to create simulations of another consciousness, and how wearable technology can amplify holistic experiences.

Keiken Artist Collective

Keiken is based in Berlin and London and gets its name from the Japanese word for “experience”. Lived experience is at the heart of the collective’s synergistic working process. Three artists from different diasporic backgrounds, Tanya Cruz, Hana Omori and Isabel Ramos, founded the collective in 2015. Keiken are interested in the nature of consciousness and existence, fascinated by alternative visions of the future in the intersections between technology and the real world. The collective’s work centres on artworks and themes in which bodily experiences often expand beyond the boundaries of the real world to construct different speculative futures. Keiken works across film, gaming, installation, extended reality (XR), blockchain, and performance, while they also develop their own forms of technology.

Keiken are the first recipients of the CHANEL Next Prize awarded to them in 2022. They are currently working at the Somerset House residency in London. Their works have recently been exhibited at such art institutions as KANAL — Centre Pompidou, Brussels (BE); Helsinki Biennial (FI), HAU Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin (DE), and C/O Berlin (DE); Wellcome Collection, London (UK); ARKO Art Center, Seoul (KR); Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf (DE); Onassis Foundation, Athens (GR); Photographers Gallery, London (UK) (2022); and the 2nd Thailand Biennale (TH).

________________________________________________________________

Spirit Systems of Soft Knowing ༊*·˚ is site-specifically created as part of a thematic collection exhibition focusing on emotions. It inaugurates Amos Rex’s triennial series of commissioned works that make innovative use of and critically examine technology.

Production team:

Creative direction and lead artists: Keiken

Production: Alexander Boyes

Interactive design: Edwin Dertien

Silicone womb fabrication design: Chris Fitzpatrick

Haptic womb soundscape & surround sound: Waveovspace

Spatial and installation design: Sebastian Kite

Projection visual design: George Jasper Stone

Studio management: Hekate Studios

Foundational haptic and silicone wearable research and development in collaboration with Ali Ball, Studio Above & Below, Lucy Page, Agf HYDRA 2021–22

Art from hundreds to thousands

Amos Anderson (1978–1961) was a businessman, newspaper publisher and passionate lover and patron of culture. During his lifetime, he was influential on the Finnish art scene, generously supporting both visual arts and theatre. Now, his legacy has made it possible to create and run Amos Rex – he is the originator of our collections.

Anderson founded the art association known as Föreningen Konstsamfundet in 1940 with the idea that, after his death, it could use his considerable wealth to support and foster art. Anderson left his entire estate to the association on certain conditions: his will stipulated that two art museums were to be set up, one in his home and office building on Yrjönkatu Street, Helsinki, and the other in Söderlångvik, his summer residence on Kimito Island. Both museums were to display works that were either in his collection or subsequently acquired for it. By the time of his death in 1961, Anderson had amassed a total of 438 works of art: paintings, sculptures and graphic prints, as well as a separate collection of medals.

In 1965, the Amos Anderson Art Museum opened on Yrjönkatu Street. At that time, the collection consisted of old European art, Finnish art from the turn of the 20th century to the end of the 1940s, and post-Second World War artworks. In tandem with this, rules were created for building up the collection, specifying that, in the future, older works were only to be added in exceptional cases, and that art from before the 1910s was to be avoided altogether. The emphasis was to be on the latest Finnish art; Konstsamfundet’s mission was expressly to support Finnish visual art and living artists. The rules were later further refined by, for example, accentuating the artistic quality of the works, larger sets of works, and acquisitions of Finland-Swedish origin.

During Museum Director Bengt von Bonsdorff’s long tenure, from 1964 to 2001, acquisitions and donations rapidly expanded the collections, by some 50–100 works a year. The first abstract works were purchased in the early 1960s. These laid the foundation for an acquisition policy that favoured young and experimental art, with a particular emphasis on painting, but also on graphic art. Alongside contemporary art, the collection of earlier Finnish art was also augmented, and soon the Museum held quite a comprehensive sample of Finnish modernism. The international dimension of the acquisitions was mainly reflected in foreign graphic prints bought from in-house exhibitions. The Amos Anderson Art Museum managed the collections until 2018, when the task was taken up by a new museum, Amos Rex.

Today, the collection comprises more than 6000 works. It consists of both the original collection acquired by Amos Anderson and new acquisitions and donations made over the years. The museum’s holdings also include Sigurd Frosterus’ representative collection of post-impressionist art, which is on permanent display at Amos Rex. An extensive collection of Birger Carlstedt’s art and a body of several hundred works by the sculptor Felix Nylund further constitute a significant part of the collection.

In April 2001, Bengt von Bonsdorff passed the Museum Director’s baton to Kai Kartio, who again had his own views on how to expand the collection. Another new era in the history of the Amos museums and collections has begun, as Kieran Long has taken over as Museum Director.

Kaj Martin,

Head of Collections

![]()

Kai Kartio and Kaj Martin examine Anu Tuominen’s artwork Carrot Purée at Four Thirty. Photo: Cata Portin / Konstsamfundet

In my time as Director of the Amos Anderson Art Museum from 2001 to 2015, Konstsamfundet granted a nice annual sum for expanding the art collection. Thus, the purchase of art continued, even though the collection was no longer prioritised as it was in the Museum’s early decades. Acquisitions were made primarily from the Museum’s in-house exhibitions. I also did my best to keep up with the galleries in Helsinki, especially the more marginal ones, and with emerging artists. A guilty conscience ensued, since I missed a lot in my haste. All proposed acquisitions were approved by Konstsamfundet’s museum committee – this being something of a formality; in practice the decisions were mine.

When construction of Amos Rex began in 2015, it was decided to concentrate all resources on it, and to suspend both art purchases and the receipt of donations. Since the completion of the new museum, acquisitions have occasionally been made from in-house exhibitions, and a couple of substantial donations have been accepted.

“I feel, for now” mirrors my acquisition policy well. I bought a work if I felt like it and if it fit the budget. I am still proud of my acquisitions, even though, looking back, I sometimes wonder what I was thinking at the time. But that really was the way I felt, at that moment.

Kai Kartio,

Museum Director 2001–2024

For Children: Meet Ou!

Here’s Ou. Ou is special because usually only children can see it. Ou was born at the same time as the Amos Rex, and it still lives there.

Have you made your own sightings of Ou in the museum? A tip: at least one place that Ou can almost certainly be found is in the museum’s cloakroom, where Ou has built a nest.

Museums collect works of art and carefully look after their collections. Do you collect something? What is it? Ou likes to collect tiny little stones that occasionally fall from museum guests’ shoes.